Projects at KU

Our lab is focused on the lifecycle development of brain-computer interfaces for speech and communication that includes three major areas:

- Investigating the neuroscience of speech and communication using electrophysiology and modeling

- Development of brain-computer interface technology for both fluent speech synthesis and for accessing current augmentative and alternative communication devices

- Translating BCI technology into paradigms and frameworks consistent with current clinical best practices in augmentative and alternative communication

On This Page

- A Brain Computer Interface Controlled Speech Synthesizer

- Controlling Augmentative and Alternative Communication Devices with BCIs

- Neural Correlates of Vowel Identification

- The Readiness Potential and its Application for BCI

- Collaborating Projects

- The Prosodic Marionette

- Electrocorticography of Continuous Speech Production

- The Unlock Project

A Brain Computer Interface Controlled Speech Synthesizer

This project is focused on developing and testing a motor imagery BCI that converts changes in the brain’s sensorimotor rhythm into speech formant frequencies for instantaneous continuous speech synthesis. Supported by the NIH: R03 DC011304 (PI: Brumberg)

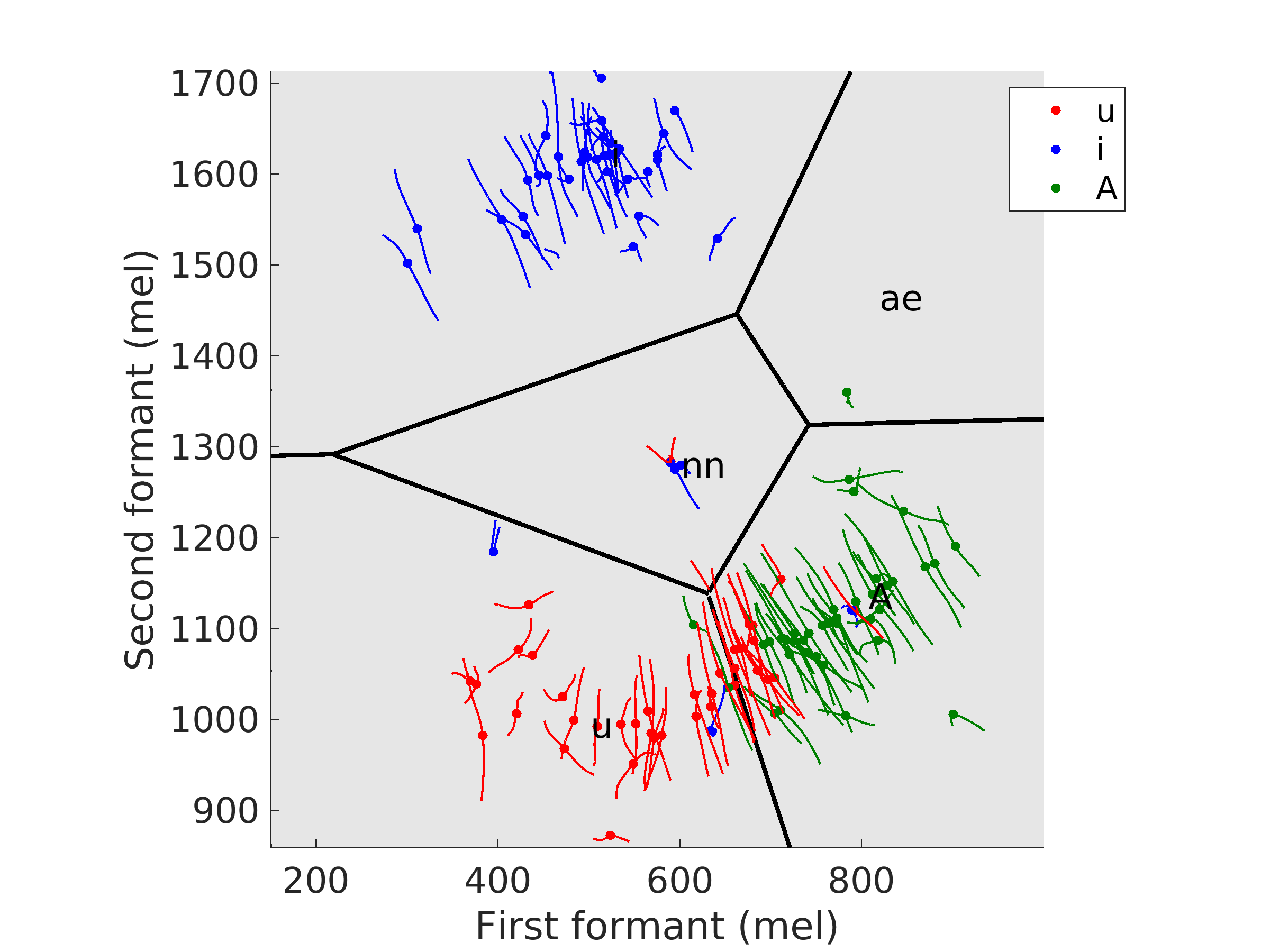

In this project individuals are taught how to control a 2D formant frequency speech synthesizer to produce speech sounds with continuous and instantaneous audio-visual feedback. Formant frequencies are a robust, low dimensional representation of the energy produced during speech, and can be used to acoustically characterize all vowel sounds. Here, an adaptive filter (Kalman Filter) brain-computer interface translates the sensorimotor rhythm into 2D formants for display on the screen and real-time synthesis for auditory feedback. Individuals can change the 2D formants by imagining moving their left and right hands, and feet. Specifically, left hand imagery will move the synthesizer toward an UW sound (like who'd), right hand toward an AA sound (like hot) and their feet toward an IY sound (like heed). The image above illustrates formant frequency trajectories produced by a single participant while controlling the BCI. Trajectories are color coded to the true intended vowel.

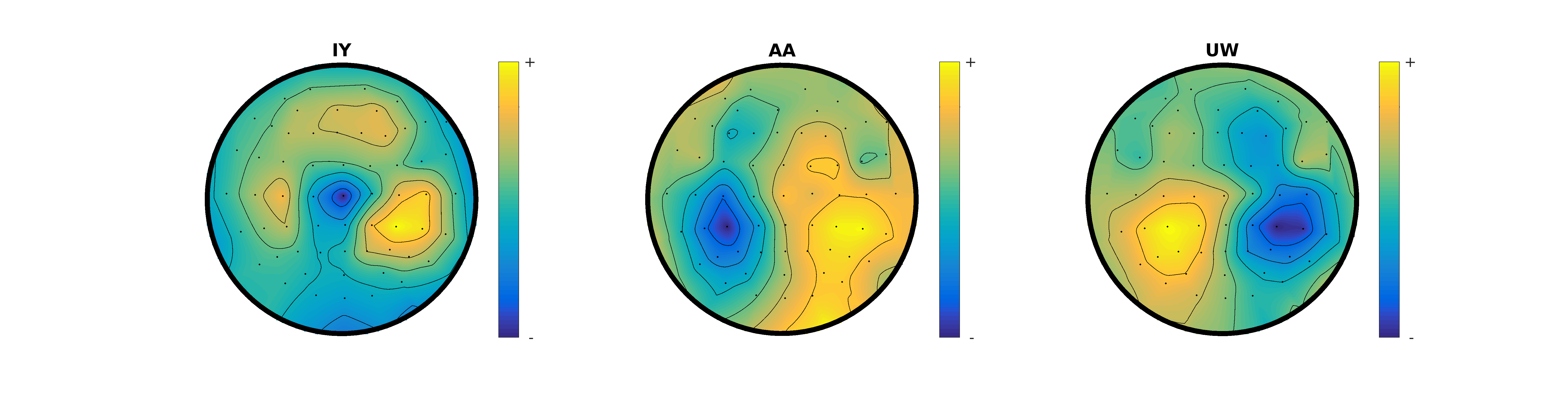

The above images are scalp topographies of EEG activity used for motor imagery control of the formant synthesizer - up is toward the nose. The BCI converts the resulting changes in the sensorimotor rhythm into formant frequencies for output.

Video: A Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interface for Real-Time Speech Synthesis

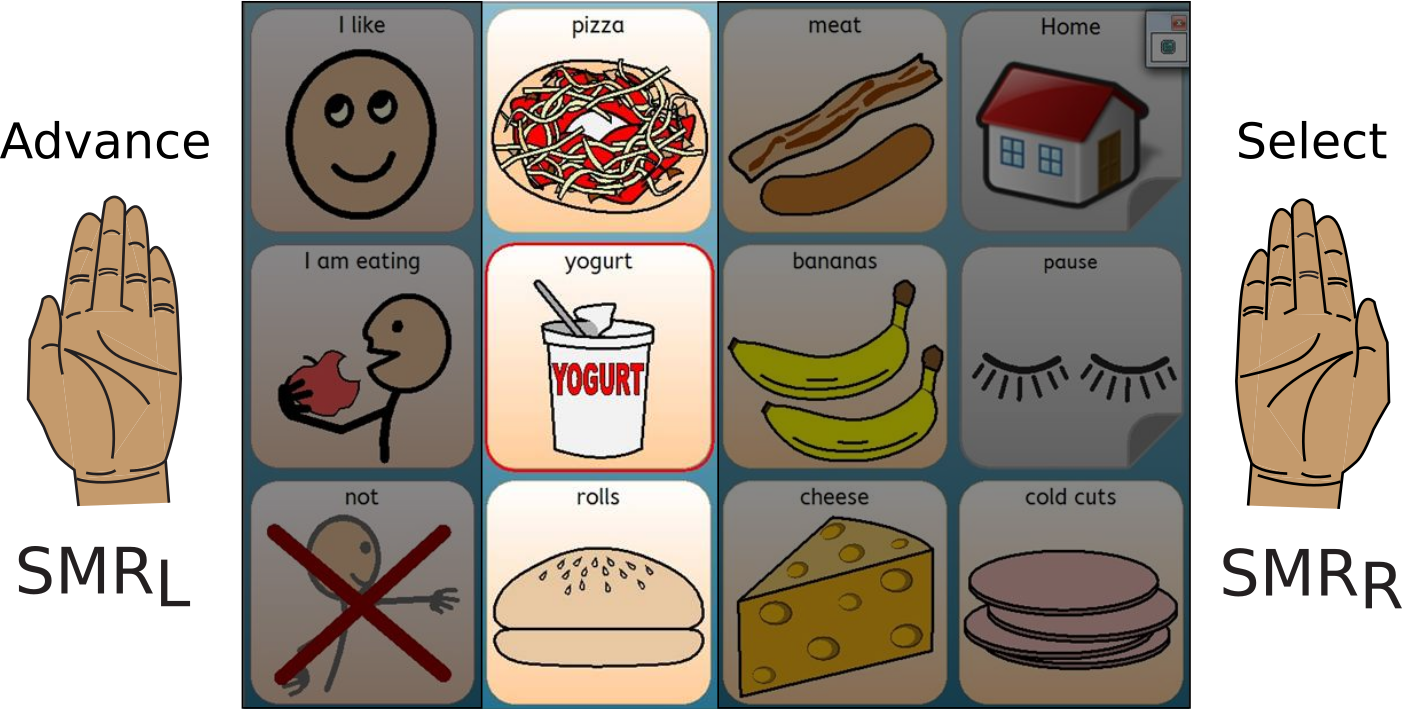

The video below is a playback of example trials from a participant using the formant frequency brain-computer interface. The 2D display represents the first and second formant frequencies with locations provided as landmarks for four vowels IY, AE, UW, AA. During a trial, one of the vowel landmarks will be highlighted in yellow indicating the vowel to be produced. The participant then imagines the correct motor control to achieve the vowel output (left hand moves a cursor and synthesized acoustic output toward UW, right hand toward AA and foot imagery toward IY). The BCI predicts a formant frequency pair at each time point, updates a visual cursor and synthesizes the current sound for participant feedback.

Brumberg, J. S., Pitt, K. M., and Burnison, J. D. (2018). A non-invasive brain-computer interface for real-time speech synthesis: the importance of multimodal feedback. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 26(4), 874–881. doi:10.1109/TNSRE.2018.2808425

Controlling Augmentative and Alternative Communication Devices with BCIs

A major goal of the lab is to provide BCI control to commercial AAC devices through collaborations with industry partners, federal agencies, foundations and current users of AAC. This project also focuses on the development of appropriate screening and assessment tools for the most appropriate selection of BCIs for accessing AAC. Supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (PI: Brumberg), University of Kansas New Faculty General Research Fund (PI: Brumberg) and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation: New Century Scholars Research Grant (PI: Brumberg)

Tutorial: BCI as an access method for AAC

Translation of BCI devices into clinical practice may be enhanced by increasing outreach to speech-language pathologists and other AAC specialists. This tutorial is intended to provide a broad background on BCI methodologies, with particular emphasis on areas of overlap with existing high-tech AAC and AAC access techniques by answering questions in 6 topic areas:

- How Do People Who Use BCI Interact With the Computer?

- Who May Best Benefit From a BCI?

- Are BCIs Faster Than Other Access Methods for AAC?

- Fatigue and Its Effects

- BCI as an Addition to Conventional AAC Access Technology

- Limitations of BCI and Future Directions

We end with broad conclusions important for SLPs and other AAC professionals. Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders R03-DC011304, PI: J. Brumberg), the University of Kansas New Faculty Research Fund (PI: J. Brumberg), and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation New Century Scholars Research Grant (PI: J. Brumberg)

Brumberg, J. S., Pitt, K. M., Mantie-Kozlowski, A. & Burnison, J. D. (2018). Brain-computer interfaces for augmentative and alternative communication: a tutorial. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 27(1). 1-12. DOI:10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0244

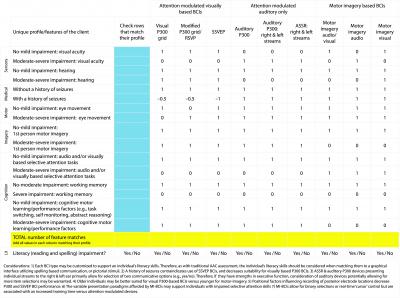

Developing AAC Feature Matching Guidelines for BCI

Feature matching is the accepted best practice for ensuring needs and preferences of individuals who use AAC are being met by any AAC intervention. As an access method for AAC, feature matching also applies to BCI, perhaps moreso given the wide variety of BCI paradigms available. In this project, we developed a feature matching tool that when combined with appropriate screening / assessment can be used to help identify BCI options that best match individual neurological characteristics and communication needs for additional live trial-based evaluation for final selection. We explore these guidelines using three hypothetical cases SLPs are likely to encounter in their work. Interviews with AAC and BCI specialists revealed seven major areas of consideration:

- Sensory: visual acuity and hearing sensitivity.

- Medical considerations: for example, history of seizures (important for some sensory BCI techniques), use of medications.

- Motor: oculomotor (eye) movement and absence of involuntary motor movements.

- Motor imagery: ability to perform first-person motor imagery, presence of neurological activity related to movement imagery.

- Cognition: attention, memory/working memory, cognitive and motor learning performance factors (e.g., task switching, self-monitoring, and abstract reasoning).

- Literacy: reading and spelling.

- General considerations: physical barriers, age, device positioning, and training

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders R03-DC011304, PI: J. Brumberg), the University of Kansas New Faculty Research Fund (PI: J. Brumberg), and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation New Century Scholars Research Grant (PI: J. Brumberg)

Pitt, K. M. and Brumberg, J. S. (2018). Guidelines for Feature Matching Assessment of Brain-Computer Interfaces for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(3). 950–964. doi:10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0135

Examining Sensory Interactions With BCI Performance

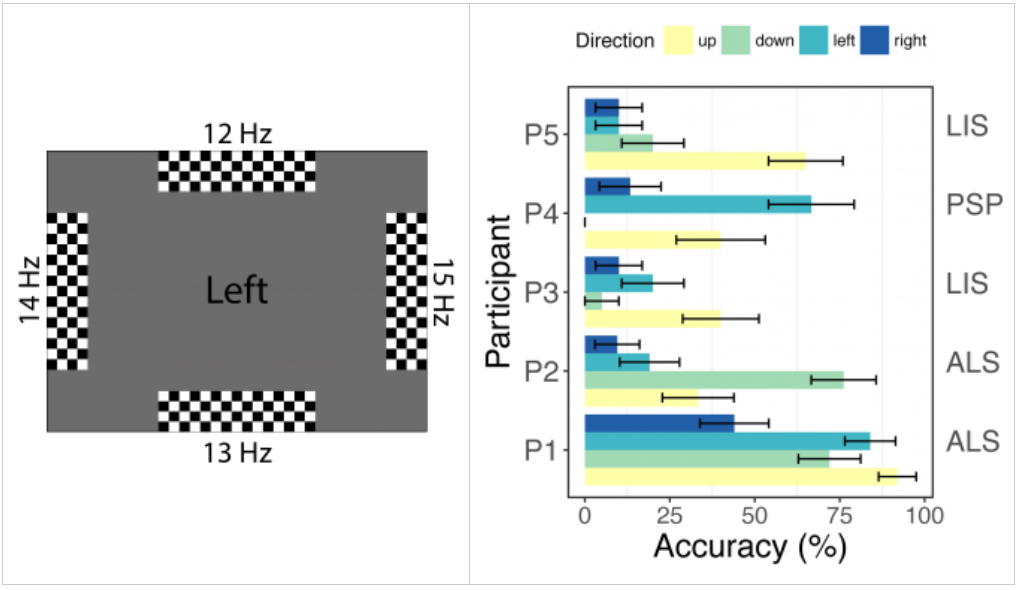

In this project we investigated the impact of oculomotor deficits for steady state visually evoked potential BCI performance in three populations with specific oculomotor impairment (ALS: idiosyncratic, Locked-In Syndrome: impaired horizontal movement, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: impaired lower visual field). Results from this project are summarized below. Participants with the least amount of movement and cognitive ability performed with lower success. In addition, performance was linked to placement on the visual screen according to visual abilities of the participants. For example, the participant with PSP was unable to see in the lower visual field and had a 0% response to that direction.

Brumberg, J. S., Nguyen, A., Pitt, K. M., and Lorenz, S. D. (2018). Examining sensory ability, feature matching, and assessment-based adaptation for a brain-computer interface using the steady-state visually evoked potential. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1–9. DOI: 10.1080/17483107.2018.1428369

Neural Correlates of Vowel Identification

Motivated from our work on a BCI controlled formant frequency speech synthesizer, this project investigates how auditory event related potentials change as adults listen to vowel sounds of varying quality and distinctiveness. A second goal is to determine whether these ERP changes can be used in a real time BCI for formant synthesis.

The Readiness Potential and its Application for BCI

Motor-based BCIs require not only the ability to interpret motor execution or imagery related neural activity into control signals, but they must also do so only when the users intends. We are investigating the readiness potential as a possible neural signal of upcoming movement intention.

Collaborating Projects

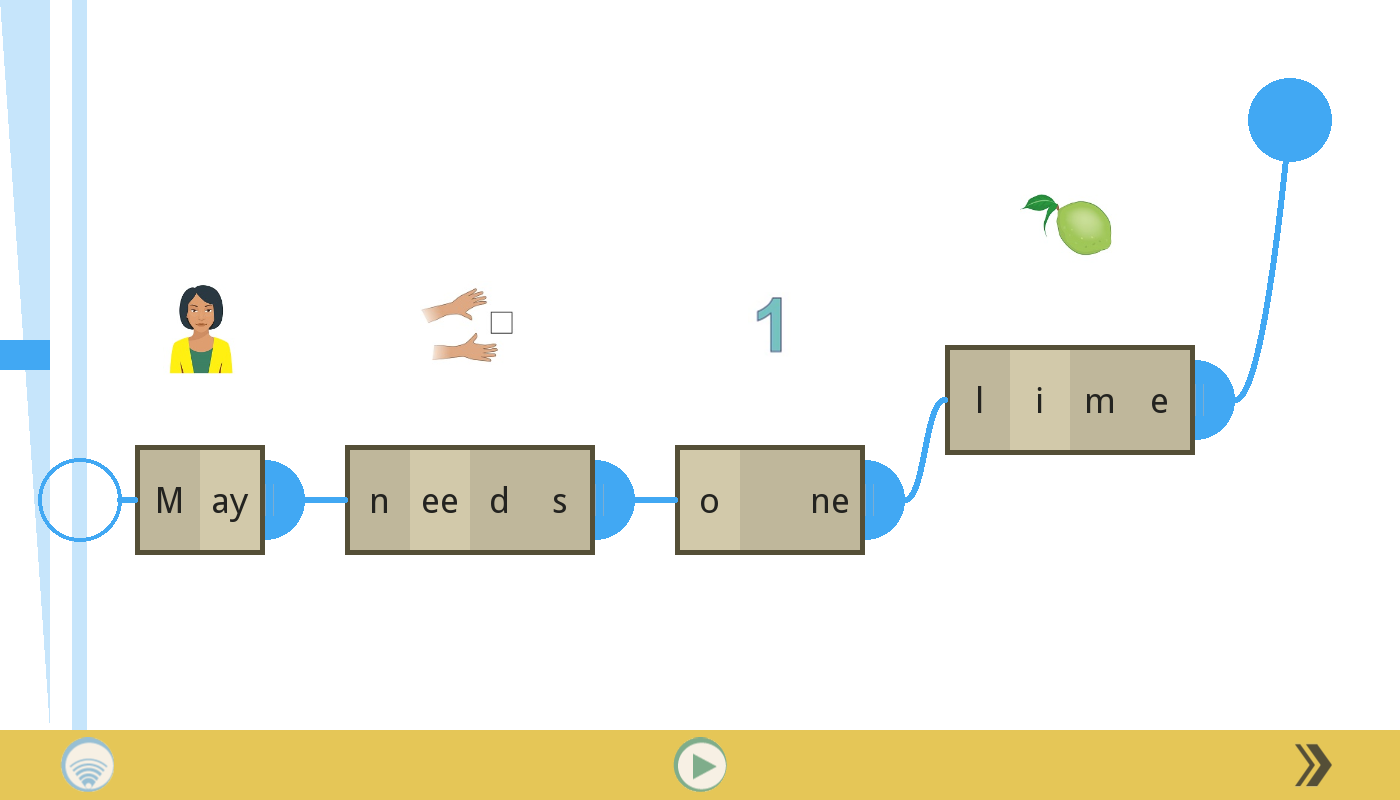

The Prosodic Marionette

In collaboration with the CADLAB at Northeastern University. The Prosodic Marionette is a novel visual-spatial graphical interface for manipulating the acoustic and temporal cues involved in linguistic prosody. We are investigating prosodic knowledge in two populations: 1) typically developing children and 2) adults with congenital and acquired neuromotor impairment.

Electrocorticography of Continuous Speech Production

In collaboration with the Schalk Lab. By using electrocorticography we are able to sample the brain’s neuroelectrical activity at incredibly fine spatial and temporal resolution necessary for studying the neural dynamics of continuous speech production.

The Unlock Project

In collaboration with CELEST at Boston University